I just started reading a book called This Land Is Our Land. I'm only 20 pages in, but things are already clicking.

“The land remembers,” writes author Jedediah Purdy

Land has become the lens for much of how I see the world.

We are intimately intertwined with the history of land. It dictates and determines who we are, at almost every level. But the thing that occupies most of my brainspace is the fact that for as much as land shapes us—we manipulate it as well.

We shape the land with laws. With treaties and covenants. With narratives. We rake the coals of commerce over the very idea of what land is, and is not—who it belongs to, and who it does not.

And we’ve done this for so long that, eventually, the true nature of land actually fades into the recesses of memory, until it’s left with only a masquerade—the farce that this eventuality was as predestined and inevitable as fate itself. That this, is the way it always has been and always will be.

“What do we remember of it?” Purdy writes, about land. “Every political contest over claims on the land is, in part, a contest over what will be remembered and what will be forgotten. With forgetting, the way things are sinks into the land itself, as if it became nature.”

Of course, if we’re lucky, forgetting can beget remembering. Or, at the very least, the chance to remember. And that’s where much of my work has been trained over the last 8 years. It has been about investigating and digging, and remembering the pieces.

Some of these pieces have been buried, intentionally hidden or obfuscated. Some have been closely guarded, through generations, for fear they would be dismembered and corrupted, as so many narratives have been. And it is through these pieces that I begin to see stories. They emerge across time, and space, and slowly, within these stories, I find memory and, ultimately, identity.

It’s been 20 months since I last wrote a newsletter. Life got fuller, I think. It forced the hard question of—with more demands on my time, what do I focus on?—and the even harder question of—what do I NOT focus on? Clearly this newsletter was one of the latter. But that’s changing with the seasons, and the platforms.

So, as I make the switch from Mailchimp to Substack, I’m hoping to share more of my life—my work, my process, my digging, my thoughts—and how history is present, whether we choose to see it or not. It is all around and under us. All we must do is remember.

First, a catch up. Here’s some of what I’ve been up to over these last many months:

Last October, I celebrated two years of being full-time at the JSAAHC.

Back in 2016 I started working on JSAAHC projects with the launch of an oral history project that Virginia Humanities funded. In 2017, I launched Mapping Cville, which led to the Black Land Repository, which led to the creation of the Center for Local Knowledge (CLK), the JSAAHC’s community-driven research arm. The CLK bridges the gap between academic research and community storytelling, using primary sources and oral histories to support Black communities as they preserve and promote their own narratives.

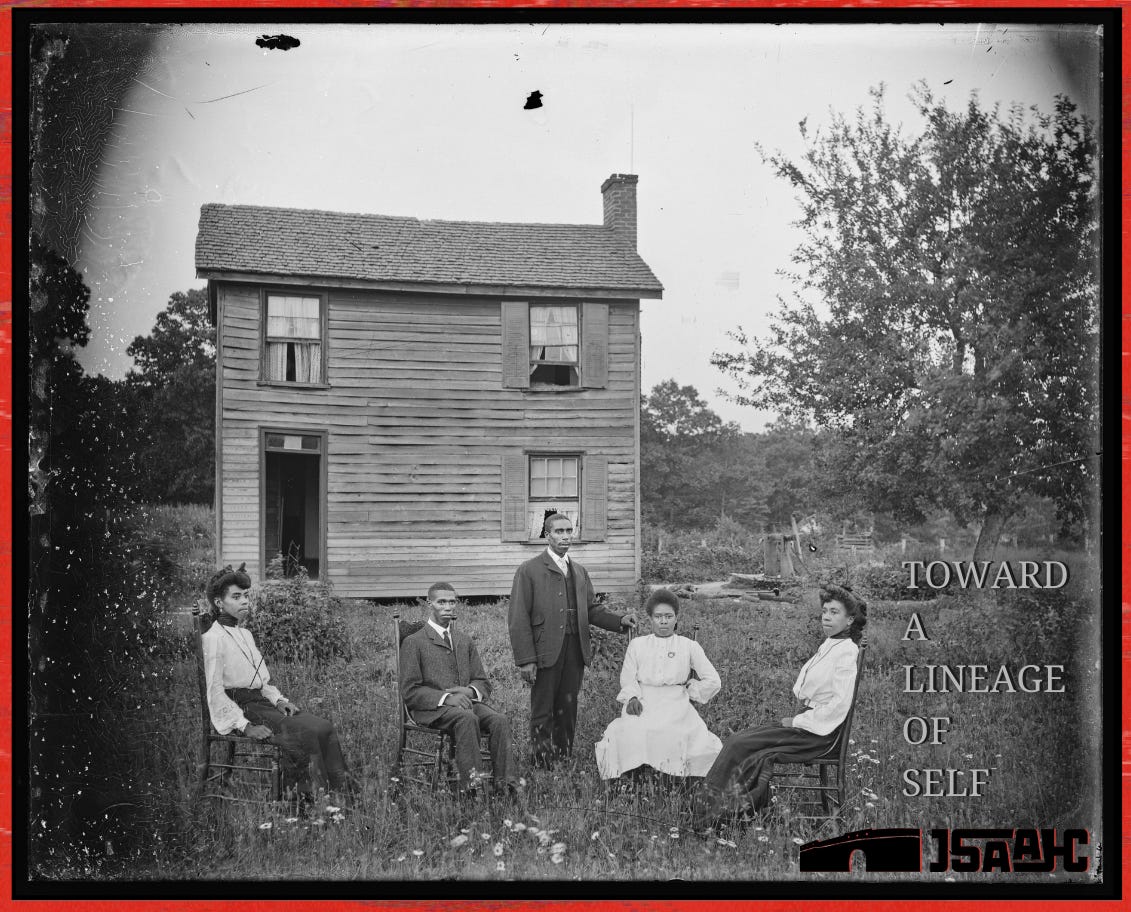

A key example of this work came to fruition recently when we launched Toward a Lineage of Self, a permanent exhibit of +120 stories that detail Charlottesville’s early development through an interactive map.

Sarah Sargent wrote about it in C-Ville Weekly:

“With photographs and descriptions, the map breathes life into the past, enlivening the facts it lays bare. The map has three categories: community, civil rights, and discrimination—and what emerges is a picture of a vibrant, well-organized, and prosperous community that supported its members, and when discriminatory practices were introduced, joined the fight for civil rights.”

[The work was funded through a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, which the Trump Administration has started to dismantle.]

Portions of this history have been known, but often in isolation.

For instance, who was the first Black property owner in Vinegar Hill? Back in 2019, we found records showing that John West bought land there in 1870 for $100. We also found that the land that became Vinegar Hill was originally a plantation.

But what we didn’t know was—how Vinegar Hill became a neighborhood? John West bought land there, and then what? What else did John West buy?

We also didn’t know the many dealings of Charlottesville first Black real estate collective. Launched in 1889, the Piedmont Industrial and Land Improvement Company purchased 15 lots on the west side of Charlottesville, near present day Booker T. Washington Park. The area became known as Kellytown, named after Alexander Kelly, a plasterer and the area’s first recorded Black property owner.

In 1995, Kelly’s great grandson, Joseph Kelly, Jr. in an oral history, said that chestnut trees lined the dirt road (Barracks Road) that ran through Kellytown. He recalled a nearby apple orchard, cherry trees, and a slaughterhouse. Neighbors had milk cows and gardens with cantaloupes and watermelons. In the summer he and his friends would dam Schenk’s Branch and swim…. (Read more here)

I’ve been trying to use social media—mostly Instagram—to tell better stories too. Like this video reel I did about the Locust Grove neighborhood’s evolution from plantation to racially restricted neighborhood.

Or this one I did about the Black neighborhood called Preston Park, which was created a year after the city passed a racial segregation ordinace, and where the Preston Plaza shopping center sits today.

Or this one, about a 6-ft long black metal bench at the southern tip of South Carolina’s Sullivan Island. It looks across the water towards Charleston and was placed there in 2008 by the Toni Morrison Society as the first installation in its “Bench by the Road” project.

One of the most transformational pieces I’ve read about Charlottesville’s history was written in 2014 by community organizer Karen Waters.

It’s about the segregation ordinance Charlottesville City Council passed in 1912, and details how that ordinance overlapped with developments in infrastructure and access to municipal resources.

Last year I published an essay in the book After Emancipation: Racism and Resistance at the University of Virginia, in which I tried to build with her amazing research to take a deep hard look at the eight White City Councilors who voted to pass the ordinance. [I uploaded the essay here]

Over the better part of a year, I researched and wrote this 4,000-word entry for Encyclopedia Virginia on Urban Renewal in Charlottesville, which explains how federal and local governments between 1950-1965 conspired to destroy the Black neighborhoods of Vinegar Hill, Cox’s Row, and Garrett Street. It’s part of EV’s larger series on Urban Renewal in Virginia.

Encyclopedia Virginia is a product of Virginia Humanities, which, as we saw last week, the Trump Administration moved to gut.

Earlier this year, I helped write a grant for the JSAAHC asking the National Endowment for the Humanities to fund a public history program we’re trying to launch to train 100+ public housing residents to research the land’s history where they live, as well as their own family’s history, and then use that research to build curriculum for K-12 public school students.

On an encouraging note, Lorenzo and I screened Raised/Razed at the Paramount Theater for more than 1,000 Eighth Graders in the Albemarle County Public School system.

And that same month, I worked alongside Andrea and Sherry at the JSAAHC to give tours of Vinegar Hill to more than 100 First Graders from Baker-Butler Elementary School in Albemarle County, and then 100 First Graders from Trailblazer Elementary School in the City. So the learning hasn’t stopped.

One of the most satisfying moments came with a day of learning I organized for more than 200 students in 11th Grade English classes at Charlottesville High School, my alma mater.

In the morning, I led half of the group downtown where we had seven amazing community interpreters up and down the pedestrian mall sharing narratives of Black history that are hidden in the local landscape, while the other half of the group stayed at the JSAAHC. There they divided into five classrooms to engage in conversation with incredible community scholars like Carmelita Wood, Sarad Davenport, Mark Bell, Frank Walker, Vizena Howard, Eddie Harris, James Bryant, and Waki Wynn. And then the groups ate lunch and rotated. [CHS wrote an article about it here]

Last but not least, as a sign of more to come, I edited together a short 20-minute video for Trinity Episcopal Church, where my mother attends. It pulls from a dozen wonderful oral histories they have done over the years, as they trace more than 100 years of faith-based community activism.

My hope it to make these newsletters shorter and more frequent.

I will always look at land in some shape, form, or fashion, but I also want to use this space to think broader—about class and capitalism—about taking care of parents who, like all of us, are getting older—about the daily stories that connect us to each other.

As with all best laid plans, the proof will be the thing itself, so we shall see. But one thing is for sure, none of this would be possible without my village, or as Purdy says: “All writing is a memorial of intellectual debt and gratitude.”

So, thank you. I mean it.

Love this!! And please always keep me in the loop about anything you're doing with Cville Schools so that I can spread the good news. TY!!

Thank you for sharing these treasures, Jordy. The Trinity video is priceless!